Building 5e wizards in 2024

How I designed five nerdy magicians for Subclasses Revivified

Welcome back to Sebastian Yue’s Newsletter! My brain is buzzing with game design thoughts that I want to get down and this is the perfect place to do it. Keep reading if you want to know more about how I (re)designed a bunch of wizard subclasses for 5e!

Recently, I had the opportunity to contribute to a book called Subclasses Revivified, which updates the rest of the 5e subclasses that weren’t included in the 2024 Player’s Handbook—all 69 of them, to be precise. Nice.

I was selected to write five wizard subclasses: Bladesinger, Chronomancer, Enchanter, Gravitist, and Leximancer. I’m pleased with the designs I was able to come up with in a relatively short span of time; we wanted to launch as close to the release date of the Player’s Handbook as possible. This post is a peek behind the scenes; I’ll share the challenges of designing for the 2024 rules in general, and go into my design process for each subclass in detail.

I brought my design experience from games other than D&D and my familiarity with other systems to inspire and create new mechanics for 5e, which I’ll also get into. I’m also sharing a couple of resources that I used while researching and working on this project.

General challenges

The biggest challenge for me was that there’s no publicly available 2024 style guide. While the current D&D House Style Guide is available on DMs Guild for free, no such rules are out for the 2024 version. Adam Hancock, of whom you likely know from their excellent work on the Elf and an Orc Had a Little Baby series, is also the project lead for Subclasses Revivified. He’s an experienced editor and a great project manager; he mastered the 2024 rules within days and created a preliminary style guide for us.

There are A Lot of capitalised terms in the 2024 rules, along with more than a handful of mechanical syntax changes. I am so used to writing and editing for the 2014 rules that even being cognisant of the changes, I found myself defaulting to the 2014 wording. It’s hardwired into my brain at this point. I’m glad for Adam’s diligence—they caught so many of my errors.

Additionally, the 2024 subclasses each have a meta-line that summarises what they can do; for example, Learn the Secrets of the Multiverse for the Diviner wizard and Create Explosive Elemental Effects for the Evoker wizard. I wrote this line last for every subclass I designed, because it was difficult to condense the essence of the subclass into so few words, especially when I wanted to avoid repeating key words in the flavour paragraph that follows.

Balance and restructuring also presented challenges; 2024 characters are noticeably more powerful than 2014 characters and my wizards had to be strong. Also, all classes now get their subclasses at level 3, which required some movement, but wasn’t as disruptive to me as I imagine it was for the cleric, sorcerer, or warlock designers.

Now, each subclass. Adam encouraged us to innovate rather than replicate, and to take the opportunity to address pain points with existing subclasses. This project was a ton of fun, and I’m immensely grateful to Adam and the rest of the team for such a great experience.

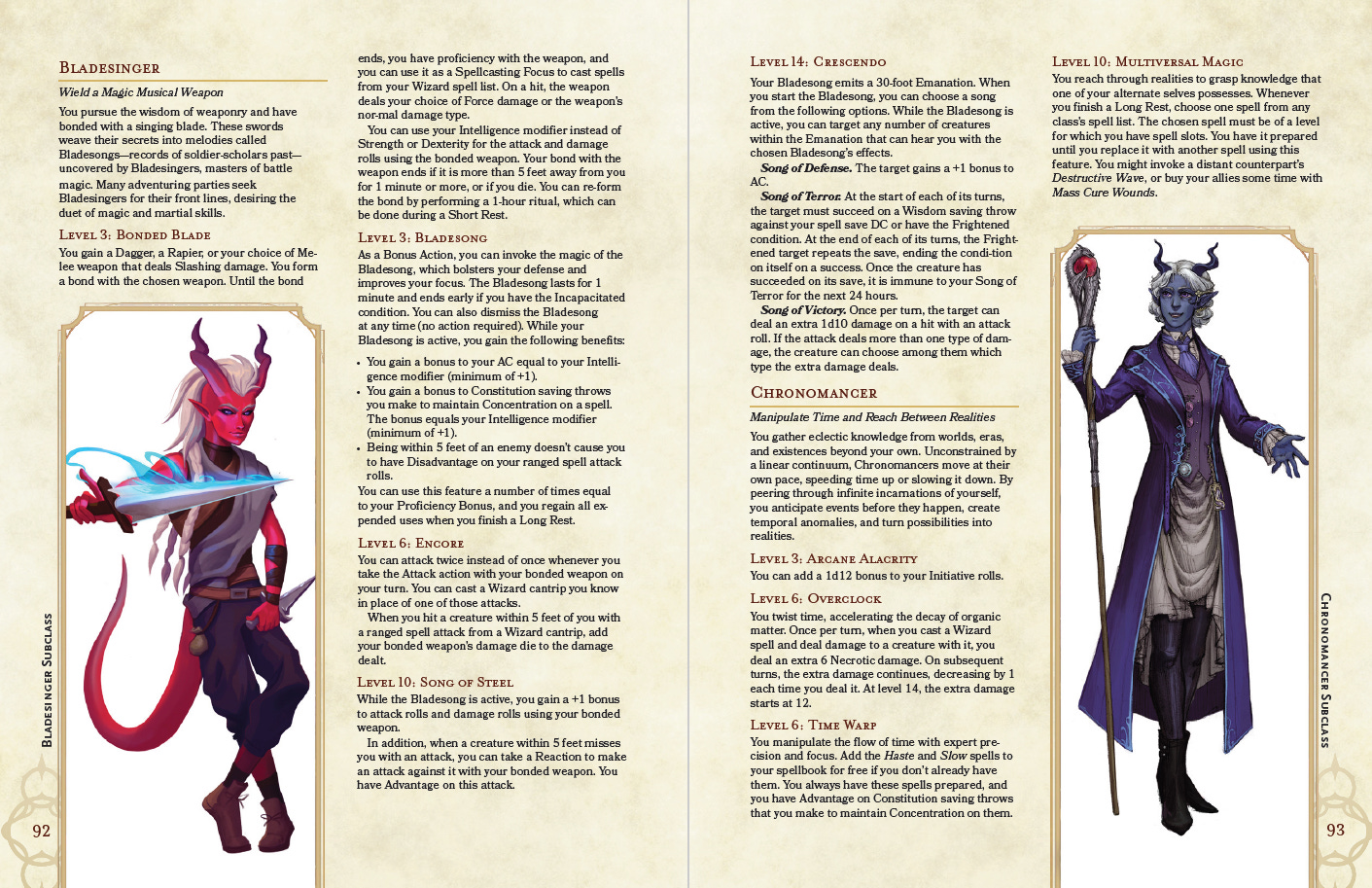

Bladesinger

Of all the wizard subclasses I designed, I am least familiar with Bladesinging. Though it looks incredibly cool, I’ve never played it. It’s a powerful subclass that, as far as I can tell, hasn’t been the subject of many complaints. I felt like I had less to go on with this, which while daunting, left more room for new interpretation.

I settled on the idea that the Bladesong is a magic sword’s way of documenting the history of its previous owners and that Bladesingers are wizards who study the song and learn martial techniques, as opposed to it being a performance routine. When I was designing this subclass, I tied everything back to the blade in a similar way to how I’ve been designing the Changed playbook for the Tomb Raider TTRPG, which has a soul artifact as the source of the playbook’s power.

My Bladesinger’s early features are familiar territory; I kept the bonus to AC, as that is such a strong feature from the original subclass that the need to innovate didn’t justify removing it.

I added the ability for the Bladesinger to cast ranged spell attacks in melee without disadvantage, as I noticed that the new Crossbow Expert feat now specifies that being within 5 feet of an enemy doesn’t impose disadvantage on your attack rolls with crossbows, but the old version allowed this benefit to apply to any ranged attack roll, including spell attack rolls (it was even clarified in a Sage Advice column that this was an intended benefit of the feat). I saw the opportunity to resurrect the old feat and give it to the new Bladesinger—appropriate for a front-line fighter.

I looked to the Eldritch Knight fighter and the warlock’s Pact of the Blade feature for examples of subclasses that have a special bond with a weapon. I wanted the Bladesinger to have a deep connection to their weapon, so you can’t be disarmed of it. The weapon must now be a blade (per the rules from the original, you could use a hand crossbow), can be used as a spellcasting focus, and it deals force damage for that magic vibe. You also get proficiency with it if you don’t already have it, because you deserve to be a wizard with a greatsword. The one complaint I have seen about Bladesinging is how multi-ability dependent it is, which I address with the option to use your Intelligence modifier for attack and damage rolls made with your blade, rather than Strength or Dexterity.

You still get your Extra Attack, but I sweetened the deal by letting you add your weapon’s damage to your cantrips, which ties in with using the blade as a spellcasting focus.

At level 14, you get three distinct songs, an idea that I came up with while I was taking a break and playing Baldur’s Gate 3. In that game, there’s a magic weapon called Phalar Aluve, a longsword that you can wield and get it to either shriek or sing. When the sword shrieks, your enemies get a debuff; when the sword sings, you and your allies get a buff. As I’d reflavoured this class to focus on the sword’s song, I gave the Bladesinger the ability to evoke different songs that have different effects: the Song of Defense, the Song of Terror, and the Song of Victory, two of which you’ll recognise as names of features from the original subclass.

Chronomancer

The Chronomancer is my favourite. I love time travel in RPGs and have discussed it at length before. I’m also playing a time-travelling wizard in my home 5e game, so I was stoked to hear that I’d been assigned the Chronomancer. It was the first subclass I wrote because it was the one I was most excited about.

The source material for the Chronomancer is of course Critical Role’s Chronurgy Magic wizard subclass from Explorer’s Guide to Wildemount, which is off-limits even on Dungeon Masters Guild. Consequently, I aimed to keep my Chronomancer thematically and mechanically divorced from the Critical Role version, but there were places where I preserved aspects of the original and put my own spin on the design.

I went so hard with the theme of this one. I wrote down a list of things associated with time travel and time manipulation that I wanted to explore: speeding up time, slowing down time, doppelgangers, alternate realities, time loops, base 12.

Some ideas came easily and were obvious choices; whenever I needed a number for this subclass, I chose either 6 or 12; you can add 1d12 to your initiative; you can deal an extra 6 damage with spells (which later increases to 12) and that damage has a countdown mechanic; you can maintain an effect for 6 rounds. It’s fitting that a time-oriented wizard would see the world in terms of sixes and twelves. Similarly, you get the haste and slow spells for free, and you have advantage on saves made to concentrate on them.

The original Chronurgy Magic subclass lets you add your Intelligence modifier to your initiative rolls, which you’d max out at +5. Explorer’s Guide to Wildemount also has a spell that lets you add 1d8 to your initiative roll on top of this, offering a total average bonus of +9 and a maximum possible bonus of +15. I agree that a time wizard should be the fastest in combat and getting to go first is a huge boon for any wizard, so I translated that feature into adding 1d12 to your initiative instead, both for the time theme and as a courtesy to the War Mage, which also features in Subclasses Revivified and retains the ability to add their Intelligence modifier to their initiative. On the face of things, my version is slightly weaker than the original, with an average bonus of +6 and a maximum bonus of +12, but if you’re converting your Chronurgy Magic wizard into a Chronomancer, you still have access to that spell. Therefore, you can stack the subclass feature with the spell for a 1d12 + 1d8 bonus, which averages out to +10 and maximizes at +20. How’s that for a power boost?

The Chronomancer also has a feature where, once per long rest, you can choose a spell from any class’s spell list and have it prepared. I didn’t want to step on the toes of the Lore bard or the Genie warlock, both of which can gain access to spells from other class’s lists, but I did look to them for wording and balance. Inspirations include the film Everything Everywhere All at Once, where the main character Evelyn can access skills possessed by alternate versions of herself, and a move that I designed for the Untethered playbook for Apocalypse Keys, where you can take one quality each from an alternate version of yourself (though the consequences are far more painful in that game). My goal with this feature was to introduce the narrative possibility of time travel without breaking the game.

My favourite feature is that at level 14, you can create a time loop and cast the same spell for 6 rounds in a row without expending spell slots. When the effect wears off, you gain 1 level of exhaustion per level of the spell. It’s an extremely powerful ability but the exhaustion drawback imposes a soft 5th-level spell cap, unless you want to use the feature to kill your character, which I think is a fascinating narrative choice and one that I’d love to see in action. The exhaustion mechanic is a holdover from the Chronurgy Magic subclass’s original 14th-level feature. I like how exhaustion raises the stakes and conveys how strenuous it is to bend time, balancing out this very powerful feature.

As a side note, if you want to know more about my Chronurgy Magic wizard Ptemfuzhi, my friend Morgan Eilish and I write a short story series about the campaign we play. Please be advised that the series contains NSFW content, which is listed in the tags before each story.

Enchanter

The Enchanter underwent the fewest changes of any of the wizards, as it’s based on the School of Enchantment subclasses from the 2014 Player’s Handbook. Enchantment is my favourite school of magic and I was so excited to update this one. It was important to me to preserve the familiarity of this one to align with the wizards in the 2024 Player’s Handbook. As the only “core” wizard subclass I worked on, it was the quickest for me to write.

The Enchanter gets the standard school savant feature, which in 2024 lets you add spells from your chosen school to your spellbook for free, as opposed to halving the gold and time you need to copy spells into your spellbook.

I tweaked the original Hypnotic Gaze feature slightly so it could affect more creatures and so I could play with the new Emanation mechanic. The 2024 rules define an Emanation as:

An area of effect that extends in straight lines from a creature or an object in all directions. The effect that creates an Emanation specifies the distance it extends.

An Emanation moves with the creature or object that is its origin unless it is an instantaneous or a stationary effect.

An Emanation’s origin (creature or object) isn’t included in the area of effect unless its creator decides otherwise.

I was thinking of the Enchanter as something of a pied piper; creatures that come closer to them are subject to their beguiling magic and are drawn to them. There’s a lot of potential to use this to get entire crowds of people to focus on you while your party members enact shenanigans in the background.

The biggest change is to the Enchanter’s level 14 feature, which is now a mass version of the Split Enchantment feature. It’s very effective and a good way to maximize your lower-level spell slots.

Gravitist

As with the Chronomancer, the Gravitist is my version of a mage who can manipulate gravity and space, distinct from Critical Role’s Graviturgy Magic subclass. With this one, I wanted to play with movement and the physical landscape of the battlefield.

Thematically speaking, the lower-level features fell into place quickly and in abundance with three level 3 features. You get gravity-themed spells to add to your spellbook for free, you’re immune to fall damage, and you have advantage on saves made against being knocked prone (or, “to avoid or end the Prone condition” in 2024 parlance). I think that if you can manipulate gravity, you’re not letting yourself take fall damage, that’s just embarrassing. I looked up the monk’s Slow Fall feature for reference, debated using a similar level-determined mechanic, but decided to make the Gravitist immune to fall damage, both for simplicity and because it’s situational enough that it’s not overpowered.

You can also open a tunnel and swap places with a creature on the other side; this feature was originally called Wyrmhole, which I love for the pun, but couldn’t justify keeping as it has nothing to do with dragons and was therefore misleading.

Later, you get the ability to assume a weightless form, which grants you a fly speed and the ability to hover. You also get a +1 bonus to AC in this form, and you deal extra damage when you deal damage with wizard spells. More than once did I consider naming that feature Defy Gravity, but I restrained myself.

Across the board, I phrased the rules for extra damage as “Whenever you cast a Wizard spell and deal damage, you deal extra damage…” because I wanted these features to apply even to spells that require a saving throw. I find that restricting damage bonuses to spell attacks means that I don’t get to use the feature as often as I’d like, and I like the indulgence of a fireball with a little extra.

I also gave the Gravitist the ability to create a black hole that doesn’t suck. No, really; I took Astronomy 101 in university as an elective and I learned that black holes do not in fact have any sucking power. So, this black hole deals force damage and also slows creatures inside it.

Leximancer

The Leximancer is my version of the Order of Scribes subclass. The working name for this subclass was Wordsmith but it didn’t feel magical enough, so I changed it to Leximancer. It’s vastly different to the original; I think the only thing I retained from the source was the ability to change a spell’s damage type. If you’re a Leximancer, you’re the nerdiest nerd who ever nerded. You’re adaptable and have a library in your back pocket, and your very words are all the power you need.

The Leximancer is built for utility; you have flexibility with skill and tool proficiencies and languages because you can look things up in your library, and you can change your list of prepared spells when when you finish a short rest because you can read so fast.

My favourite feature for this subclass is that you can physically make an edit to a spell you currently have prepared and change how it works. Inspirations for this mechanic were the “ruin a spell by changing one letter” games that frequently make the rounds on the internet, and the Metaphysical Amputation high advance that Lexicutioners get in Rowan, Rook and Decard’s STRATA: A Spire Sourcebook. In Spire, Lexicutioners are language assassins whose job is to eliminate dangerous languages, so players eventually get the ability to delete a word or phrase from either their character sheet or the copy of Spire that the GM is using, and the edit reshapes the rules they play by. They can use this ability only once, but the change to the rules is lasting.

The Leximancer wizard is more of an editor than a word-killer, so the emphasis is on change as opposed to destruction of language. You can remove or replace a word in a spell and until you finish a Long Rest, it functions in accordance with the new wording. This feature is also repeatable; you can use it once every 3 long rests. Notably, I encoded that you can’t edit numerals, because changing a spell to deal 1000d6 damage is no fun for anyone. I also didn’t want to encroach on the sorcerer’s Metamagic options and the way that they can extend the range and duration of their spells. If you play a Leximancer, please tell me what edits you make to your spells because I’d love to see what you come up with.

Resources

Here are a couple of resources that I found invaluable when researching these subclasses.

#JacksSplatbook

Jack’s Splatbook is a series delivered on Twitter by Jack Weighill of Dice Average RPG, in which he analyses the features of each subclass in 5e. Though the series is on currently hold, I’m grateful for the commentary Jack already gave for the Bladesinging and Chronurgy Magic subclasses. If he decides to resume the series to redo it for 2024, I’ll definitely be following. You can find Jack’s work in the Splatbook Database. Relatedly, I also highly recommend #JacksSpellbook, where Jack rates and analyses each 5e spell. That series is complete.

RPGBOT.net

RPGBOT’s 5e character optimisation guides and subclass handbooks are an excellent resource, not only for character building, but for a deeper understanding of exploits, weird edge cases, and interesting applications of many 5e rules. I’ve enjoyed the breakdowns on there for some time, and I looked up the entries for all the subclasses I was assigned before I started writing. Tyler’s insights were immensely helpful, and he’s even updating the site with optimisation guides for the 2024 rules.

Subclasses Revivified is out now on Dungeon Masters Guild.

Are you planning to design with the 2024 rules? Leave a comment if you enjoyed this post, or if you want to keep talking about wizards (I always want to keep talking about wizards).